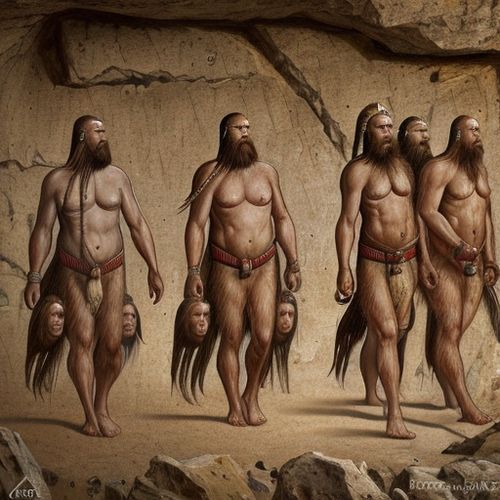

In a groundbreaking discovery, scientists have identified a fossilized jawbone found off the coast of Taiwan as belonging to a Denisovan man. This significant find, known as Penghu 1, has expanded our understanding of the Denisovans, an enigmatic ancient human species first identified in 2010. The confirmation was achieved through the analysis of ancient protein fragments contained in teeth still attached to the jawbone, a technique that has proven more durable than DNA over time.

The Discovery and Its Significance

The jawbone was dredged up by fishermen in 2010 from the seafloor 15½ miles off the coast of Taiwan. For years, scientists struggled to pinpoint its exact place in the human family tree. The confirmation that it belonged to a Denisovan man was published in the journal Science, marking a significant advancement in our knowledge of this ancient species.

Study coauthor Frido Welker, an associate professor of biomolecular paleoanthropology at the University of Copenhagen’s Globe Institute, highlighted the importance of ancient proteins in such discoveries. "We’ve determined and shown over the past couple of years that these proteins can survive longer than DNA does, and that if we have decent recovery, we can say something about the evolutionary ancestry of a specimen," Welker said.

The Denisovans: A Mysterious Species

Denisovans were first identified in 2010 through DNA sequences extracted from a tiny fragment of finger bone found in Denisova Cave in Siberia’s Altai Mountains. Genetic analysis revealed that Denisovans, like Neanderthals, had interbred with early modern humans. Traces of Denisovan DNA in present-day people suggest they once lived across much of Asia. This discovery places the Denisovans in a diverse range of environments, from the Siberian mountains to the high-altitude Tibetan Plateau and the humid subtropical latitudes.

The Journey of the Fossil

Fishermen working off the coast of Taiwan have long found ancient animal bones in their nets, relics from an ice age past when sea levels were lower, and the ocean channel was a land bridge. The Denisovan man likely lived on this strip of land that once existed between what is now China and Taiwan.

The jawbone, now identified as Denisovan, was brought to Taiwan’s National Museum of Natural Science by a collector. Study coauthor Chun-Hsiang Chang, a curator of paleontology at the museum, recognized its significance and encouraged the collector to donate or sell the fossil to the museum. A 2015 paper coauthored by Chang argued that the fossil belonged to the genus Homo, but without ancient DNA, the exact species could not be verified.

The Role of Proteomics

In 2022, Chang took the specimen to Copenhagen to work with Welker and other scientists pioneering techniques in paleoproteomics, the study of extracting proteins from fossils. Before testing the jawbone, the team sampled an elephant bone and pig bone from the same seabed area to determine the best extraction methods. They found proteins and proceeded with the extraction.

Two amino acid sequences from the proteins matched those known from the Denisovan genome. Additionally, the lab work detected a type of protein with a sex-specific peptide called amelogenin, revealing that the individual was male.

Future Implications and Discoveries

The good preservation of proteins in the Penghu 1 mandible is surprising, given its long submersion in seawater. Archaeologist Zhang Dongju, a professor at China’s Lanzhou University, noted that with the accumulation of Denisovan fossils and molecular signatures, identification will become easier. She believes more Denisovan fossils will be found and identified in the future.

Katerina Douka, an associate professor in archaeological science at Austria’s University of Vienna, described Denisovans as a paradox due to the detailed genetic information available despite the scarcity of fossils. Ryan McRae, a paleoanthropologist at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, noted that neither the Penghu nor Xiahe mandibles had wisdom teeth, suggesting a flatter jawline compared to modern humans.

Chang and his colleagues plan to revisit the 4,000 fossils in the National Museum of Natural Science’s collection, using proteomic methods to investigate whether any other fragments belong to Denisovans. This discovery not only expands our understanding of the Denisovans but also opens new avenues for future research into this mysterious species.

By Olivia Reed/Apr 14, 2025

By Sophia Lewis/Apr 14, 2025

By Noah Bell/Apr 14, 2025

By Eric Ward/Apr 14, 2025

By Sophia Lewis/Apr 14, 2025

By Sarah Davis/Apr 14, 2025

By William Miller/Apr 14, 2025

By James Moore/Apr 14, 2025

By Eric Ward/Apr 14, 2025

By Grace Cox/Apr 14, 2025

By Rebecca Stewart/Apr 10, 2025

By Grace Cox/Apr 10, 2025

By Thomas Roberts/Apr 10, 2025

By James Moore/Apr 10, 2025

By Laura Wilson/Apr 10, 2025

By John Smith/Apr 10, 2025

By James Moore/Apr 10, 2025

By Olivia Reed/Apr 10, 2025

By Eric Ward/Apr 10, 2025