The debate surrounding the 3D scanning of world heritage sites has ignited passionate discussions among archaeologists, ethicists, and cultural preservationists. As technology advances at an unprecedented pace, the line between preservation and appropriation becomes increasingly blurred. Some argue that digitizing these treasures safeguards them for future generations, while others view it as a form of cultural exploitation masked as progress.

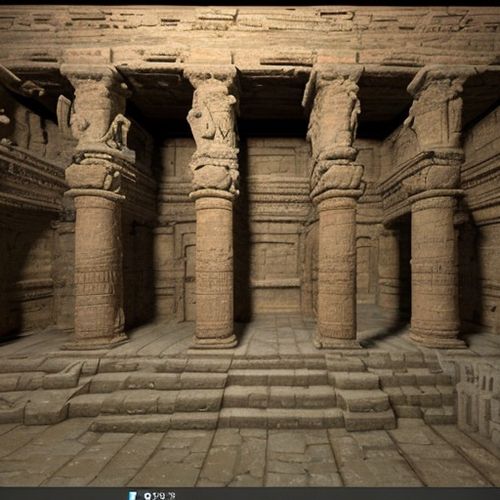

The rise of 3D scanning technology has revolutionized how we document and study cultural heritage. High-resolution scans can capture intricate details of ancient artifacts, monuments, and even entire archaeological sites with astonishing accuracy. This digital preservation seems like an obvious boon, especially for sites threatened by war, climate change, or urban development. The data collected could theoretically allow for exact reconstructions should the originals be damaged or destroyed.

However, beneath this seemingly altruistic purpose lies a complex web of ethical concerns. Who owns the digital rights to these scans? When international teams or private companies create 3D models of heritage sites located in developing nations, questions about sovereignty and control inevitably arise. The very act of scanning can be seen as extracting cultural capital from communities that may lack the resources to participate equally in these projects.

The technology itself isn't inherently problematic - it's the context and implementation that raise red flags. Many scanning projects operate under the guise of academic research or conservation while being funded by organizations with commercial interests. The resulting digital assets often become proprietary data, locked behind paywalls or used to generate profit through licensing agreements, virtual tours, or merchandise.

Cultural sensitivity adds another layer to this dilemma. Some heritage sites hold deep spiritual significance for indigenous communities. The process of scanning sacred spaces or objects without proper consultation can constitute a profound violation. Even when intentions are pure, the mechanical reproduction of culturally sensitive items through 3D printing or virtual reality displays may cross ethical boundaries that Western technologists fail to recognize.

Legal frameworks struggle to keep pace with these technological developments. Current international conventions on cultural property were drafted long before 3D scanning existed as a concept. This legal vacuum allows for scenarios where digital replicas can be created and distributed without the consent of originating communities. Some nations have begun implementing stricter controls, but enforcement remains inconsistent across borders.

The argument for democratization of culture through digital access presents a compelling counterpoint. Proponents suggest that 3D models allow global audiences to experience heritage they might never see in person, particularly for those unable to travel due to financial or physical limitations. Virtual reconstructions can also aid in education, helping students worldwide engage with history in immersive ways textbooks cannot match.

Yet this perspective often overlooks the economic implications. Many world heritage sites rely on tourism revenue for maintenance and local development. If high-quality digital alternatives reduce physical visits, communities could lose vital income streams. The technology might inadvertently create a new form of cultural consumption where privileged institutions control access to digital heritage while original stewards see diminishing returns.

The colonial undertones of certain scanning projects cannot be ignored. History is replete with examples of Western explorers and scholars removing artifacts from their original contexts under the pretense of study or protection. Modern digital practices risk repeating these patterns, just in virtual form. When foreign entities claim authority over the digital representation of another culture's heritage, it perpetuates power imbalances rooted in historical exploitation.

Some organizations have begun developing best practices for ethical scanning, emphasizing collaboration with local communities from project inception. These models prioritize capacity building, ensuring that source communities benefit from both the process and products of digitization. They also address concerns about appropriate usage, establishing protocols for culturally sensitive materials.

The conversation becomes even more complex when considering conflict zones and endangered heritage. Organizations like UNESCO have partnered with tech companies to digitally preserve sites at risk from ISIS destruction or other threats. While undeniably urgent, these rescue missions sometimes proceed without full consultation with displaced communities, raising questions about who gets to decide what deserves preservation and how it should be presented.

As the technology becomes more accessible, the potential for misuse grows exponentially. Amateur scanning enthusiasts might capture and share culturally significant sites without understanding the implications. Social media platforms already overflow with 3D models of protected heritage, often stripped of context and shared without permission. This casual circulation further complicates efforts to maintain cultural integrity in the digital sphere.

The future of heritage preservation likely involves finding a middle ground. Complete rejection of 3D scanning technology would mean losing a powerful conservation tool, while unchecked digitization risks commodifying culture. The solution may lie in developing international standards that respect cultural sovereignty, ensure equitable benefit sharing, and maintain the sacred nature of certain artifacts and sites.

Ultimately, the question isn't whether 3D scanning constitutes cultural plunder, but rather how we choose to implement it. Like any powerful technology, its ethical value depends entirely on the hands that wield it. As we navigate this new frontier, we must remain vigilant against repeating historical patterns of extraction while embracing the genuine opportunities for preservation and education that digital innovation provides.

By James Moore/Apr 12, 2025

By Grace Cox/Apr 12, 2025

By Ryan Martin/Apr 12, 2025

By Lily Simpson/Apr 12, 2025

By William Miller/Apr 12, 2025

By Michael Brown/Apr 12, 2025

By Laura Wilson/Apr 12, 2025

By Emma Thompson/Apr 12, 2025

By James Moore/Apr 12, 2025

By Emma Thompson/Apr 12, 2025

By Ryan Martin/Apr 12, 2025

By Victoria Gonzalez/Apr 12, 2025

By William Miller/Apr 12, 2025

By Grace Cox/Apr 12, 2025

By Sophia Lewis/Apr 12, 2025

By Amanda Phillips/Apr 12, 2025

By William Miller/Apr 12, 2025

By Sarah Davis/Apr 12, 2025

By Jessica Lee/Apr 12, 2025

By Emma Thompson/Apr 12, 2025