The Istanbul Biennial, one of the most anticipated contemporary art events in the global cultural calendar, has announced a striking shift for its upcoming edition. The historic decision to relocate its primary exhibition space to a decommissioned power plant has sent ripples through the art world. This move not only redefines the physical context of the biennial but also signals a deeper engagement with themes of urban transformation, industrial heritage, and sustainable cultural practices.

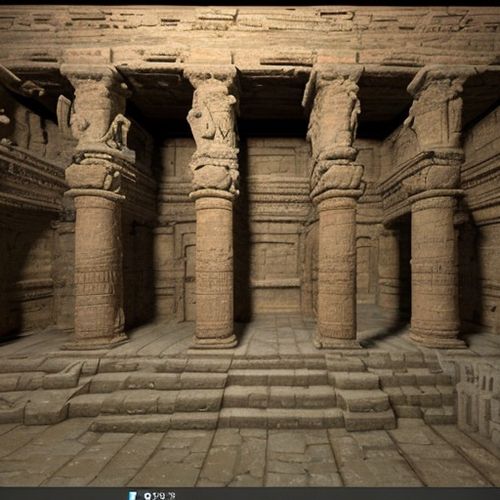

For decades, the Istanbul Biennial has utilized various iconic locations across the city, from ancient hammams to repurposed industrial buildings. However, the selection of the Silahtarağa Power Plant—a colossal early 20th-century structure that once supplied electricity to much of Istanbul—marks perhaps its most ambitious venue choice yet. The decaying grandeur of this Brutalist complex, with its cavernous turbine halls and rusted steel skeletons, offers curators an unparalleled canvas for large-scale installations and site-specific works.

The decision to occupy this post-industrial behemoth speaks volumes about the biennial's evolving philosophy. Where many international art festivals compete to secure pristine white-cube galleries or architecturally spectacular new museums, Istanbul's organizers have deliberately embraced the raw, unfinished quality of a structure frozen in time. The power plant's very fabric—its soot-stained brickwork, its labyrinthine underground passages, the haunting absence of its former purpose—becomes an active participant in the artistic dialogue rather than mere backdrop.

Local historians note the poetic resonance of this choice. The Silahtarağa facility, operational from 1913 until its decommissioning in 1983, witnessed nearly every major transformation of modern Turkey. Its furnaces burned through the final years of the Ottoman Empire, the birth of the republic, periods of military rule, and Istanbul's explosive late-century growth. To walk through its abandoned control rooms now is to traverse the physical archives of industrialization and obsolescence. Artists selected for the biennial will inevitably respond to these layers of history, with early proposals already exploring themes of energy (both electrical and political), labor invisibility, and the afterlife of infrastructure.

Practical considerations of the relocation have required innovative solutions. The plant's vast interior spaces—some exceeding 10,000 square meters with ceiling heights rivaling cathedrals—present unique challenges for climate control, lighting, and visitor flow. Rather than attempting to neutralize these difficulties, curators have incorporated them into the exhibition design. Temporary walkways will trace the paths of former coal conveyors; natural light filtering through broken skylights will illuminate certain installations; the ever-present hum of the Golden Horn's water will provide an auditory counterpoint to video works.

Environmental sustainability has emerged as a key concern in the repurposing process. The organizing foundation has partnered with green architects to implement renewable energy systems that will power the biennial without compromising the building's integrity. Solar panels discreetly placed on outbuildings, geothermal heating drawn from the nearby estuary, and rainwater collection systems demonstrate how cultural events can model ecological responsibility while working with challenging historic structures.

This venue change also carries significant urban implications. The power plant sits in the Haliç district, a once-thriving industrial zone that suffered decades of decline before recent gentrification efforts. By anchoring the biennial in this location, organizers aim to catalyze cultural activity beyond Istanbul's established arts districts while avoiding the pitfalls of displacement that often accompany such initiatives. An extensive community program will connect the international art world with local residents through workshops, educational projects, and neighborhood collaborations.

Art critics have begun speculating about how the raw industrial aesthetic might influence participating artists' work. Previous editions of the biennial have occasionally struggled with venues that felt at odds with contemporary practices—either too precious for intervention or too neutral to inspire site-responsive creations. The power plant's overwhelming physical presence virtually demands that artists engage directly with their surroundings, potentially leading to one of the most conceptually cohesive exhibitions in the event's history.

Behind the scenes, the technical team faces extraordinary challenges in preparing the space. Conservation specialists work alongside structural engineers to stabilize areas of the complex without erasing the patina of age. Asbestos abatement, lead paint removal, and careful reinforcement of crumbling concrete have consumed months of labor. Yet the team insists these efforts preserve not just a building but an important chapter of Istanbul's material history—one that can now be reinterpreted through contemporary art.

The move has sparked debate about the role of biennials in urban regeneration. While some praise the ethical considerations evident in the Istanbul team's approach, others question whether any temporary art event can meaningfully contribute to long-term development. In response, organizers have committed to leaving behind improved infrastructure and establishing a permanent arts presence in the power plant after the biennial concludes—a model that could influence how major exhibitions consider their legacy.

For visitors, the experience promises to be unforgettable. Unlike conventional gallery hopping, navigating the power plant will require physical and mental adaptation to uneven floors, dramatic changes in scale, and the constant awareness of the building's former life. This embodied experience aligns with current curatorial interests in "affective architecture"—how spaces produce emotional and psychological responses that become part of the artwork's meaning.

As installation begins, early glimpses suggest the venue is already shaping the biennial's character. Monumental works that would feel overwhelming in traditional museums find their perfect scale amid the generators' colossal footprints. Delicate pieces gain unexpected poignancy when juxtaposed with decaying machinery. The entire exhibition seems poised to become a meditation on time, utility, and the strange beauty of things that have outlived their original purpose.

This bold relocation may well mark a turning point for mega-exhibitions globally. In an era of increasing skepticism about the carbon footprint and social impact of biennials, the Istanbul model—embracing existing structures with all their complexities rather than constructing temporary pavilions—offers a compelling alternative. The success of this experiment could encourage other major festivals to reconsider their relationship with urban spaces and historical preservation.

When the biennial opens, the ghosts of the power plant will share the space with cutting-edge contemporary art. The resulting conversations between past and present, between functional infrastructure and aesthetic contemplation, may redefine what a 21st-century art exhibition can be. For now, the art world watches with anticipation as Istanbul prepares to illuminate this forgotten monument—not with kilowatts of electricity, but with the equally transformative power of artistic vision.

By James Moore/Apr 12, 2025

By Grace Cox/Apr 12, 2025

By Ryan Martin/Apr 12, 2025

By Lily Simpson/Apr 12, 2025

By William Miller/Apr 12, 2025

By Michael Brown/Apr 12, 2025

By Laura Wilson/Apr 12, 2025

By Emma Thompson/Apr 12, 2025

By James Moore/Apr 12, 2025

By Emma Thompson/Apr 12, 2025

By Ryan Martin/Apr 12, 2025

By Victoria Gonzalez/Apr 12, 2025

By William Miller/Apr 12, 2025

By Grace Cox/Apr 12, 2025

By Sophia Lewis/Apr 12, 2025

By Amanda Phillips/Apr 12, 2025

By William Miller/Apr 12, 2025

By Sarah Davis/Apr 12, 2025

By Jessica Lee/Apr 12, 2025

By Emma Thompson/Apr 12, 2025